Aligning

my politics, radicalization, and art

Substack just doubled down on their shitty, dangerous (lack of) content moderation and isn’t standing up for trans writers, but I’ve had this essay drafted for too long and I’m too annoyed to put energy into moving platforms yet. This is, in many ways, a hypocritical piece to send out given the context. The situation is also a kind of perfect illustration of the tensions and difficult questions inherent in creating art that seeks to resist and dismantle capitalism. I write about that below in the context of poetry publishing, and have many shifting thoughts about the subject.

I’ll almost certainly be moving, but perhaps what’s most frustrating about this all is how the Discourse™️ is ultimately exhausting for trans writers more than anyone (too, too many screenshots of rampant transphobia). When will our resistance be joyful, militant, creative, and affirming, and not merely reactionary and draining? We are the ones who end up leaving because we’re pissed— exactly what the transphobes want. To wear us down, take away our spaces. They are relentless and tireless in denying our right to exist, even on shitty techno-libertarian bro platforms where we just want to post hot girl poems 😭

This is a pretty long piece, the longest I’ve posted here. I wrote it in early February for a presentation I was fortunate to be invited to give by Professor Suzanne Savaria at Portland State University’s Artist as Citizen Initiative. The students watched/read the following presentation beforehand (there’s a video of me narrating, and a transcription), and then we had an amazing, lovely lively discussion about creating in community, the perverse stuntedness of the white supremacist imaginary, the revolutionary act of healing, and so much more. I’m really grateful to Professor Savaria and her co-instructor, Professor Darrell Grant, and for all the really inspiring students, artists, radicals in their class. To digging deeper, to grasping at the root (Angela Davis).

Consciousness is the art

— Cecilia Vicuña

I think writing moves towards social justice when the writer is able to name and make explicit the ideas and assumptions that they're bringing to why they're thinking about something in a certain way.

— Mary-Kim Arnold

The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible.

— Toni Cade Bambara

Hi! My name is Nico, and I’m really excited and honored to have this opportunity to learn with you all and share some of my experiences. I hope you’re well and taking care in these tumultuous times, where learning, making art, and resisting are all extra challenging. Apologies in advance for any hissing, gurgling or bubbling from my old house’s crazy radiators. They’ve really been going off lately.

So! I’m a Chilean-American transfemme nonbinary artist and I’m white Latinx, and though in the US my family is considered lower-middle-income, in Chile we now live comfortably as upper-middle class, so I hold considerable race and class privilege. I am a documentary poet and filmmaker, which to me means that my work is rooted in a variety of research practices— from family and personal history, to interventions in and with archival materials, ritual investigations and investigation rituals, to the stories of others I've had the chance to record. I could just as easily turn that around to say the I’m a poetic documentarian, because I believe, as the poet Muriel Rukeyser once said, that “poetry can extend the document.” Poetry lets us understand something more than what is said on the surface, it reveals and confronts the multiplicity of language and what can be said, revealing what can’t be said, as well.

Right now, I’m speaking to you from the ancestral lands of the Narragansett people, currently called Providence, Rhode Island. Recognizing the land is an expression of gratitude and a way of honoring the Indigenous people who have been living and working on this island from time immemorial. I don’t think we can be free or have justice on these lands until they have been returned to the Indigenous peoples who continue existing and resisting today, and I believe that will require a fundamental shift in how we relate to the land, ourselves and each other, including the abolition of private property, police, prisons and the military. This is especially important to me because I myself exist thanks to interwoven processes of colonization and resistance, violence and migration, and I carry those histories and my ancestors in my life and work.

In fact, I’d like to start with a bit of history on who I am and how I got here. I was born in Santiago de Chile in the late nineties to a father from the US and a Chilean mother. We moved to Los Angeles, CA shortly after and ended up staying far longer than intended, until we returned to Chile in 2011. There was a lot going in Chile the year we arrived, including the peak of a student protest movement that had been building for some time. High school and university students took over and occupied their campuses, holding assemblies to discuss the injustices and inequalities of the educational system, proposing and demanding alternatives, and planning incredibly creative mass protests, such as kiss-a-thons, pillow fights, and large-scale puppet shows.

The root of the problems with Chile’s education is the US-backed military dictatorship, which controlled the country until 1990. The root of the Chilean student movement’s creativity reaches back even further, to the radical leftist artists of the 60s and 70s who led a cultural revolution alongside Salvador Allende’s democratic socialist revolution that was cut short in 1973 by the coup. One of the first and most famous victims of the dictatorship’s cruelty, in fact, was the communist musician Victor Jara, whose fingers were cut off by guards before they assassinated him while he was detained as a political prisoner. Time and time again, we see fascists go after art and artists because they recognize that art has the power to change minds, build unity, and affect real change in the world.

When I started to join the still-ongoing, but by then waning, student movement in 2013, I noticed the creativity and art that I’d witnessed before had all but disappeared in march after march, where students faced brutal police repression and political blockages. Though there were still often great brass bands and dancing at protests, the media would focus exclusively on violent clashes, often instigated by the police themselves, which overshadowed student’s radical proposals. It was in the streets that a lot of my early education and radicalization happened, in conversations with friends, reading anarchist zines, and going to informal lectures and discussions. As I got more involved and wanted to contribute to the movement I was learning from, I thought bringing back some of the art would be a good way to shift the narrative away, if only for a moment, from the violence— without necessarily invalidating it as a different form of resistance. With a small group of friends and strangers from other schools, we built a large cardboard pencil, broken in two, to symbolize how the educational system was broken. Several of the leading, conservative newspapers featured photos of our pencil the next day, which felt like a small, but tangible, impact. Though most of the changes to the educational system that we demanded then have yet to be fulfilled, I think the student movement of the early 2010s set the stage for the more massive movements we’ve seen take over the country since.

Around that time, in 2015, was also when I started making short documentaries, and began asking challenging questions around representation, my positionality and gaze, and what the function of documentary practice really is, all things I continue to think about and incorporate into my work today. I moved back to the States in 2016 for college, where these questions gained even greater relevance as I learned about identity politics and, for a time, shifted away from more class-based critiques. I tried to get involved with some social justice groups on campus, as well as occasional protests that would happen, but found it quite difficult to adapt to the U.S.-college-resistance environment. The campus groups were pretty deeply entrenched in institutional practices that meant change and resistance had to play by rules that often ended up reifying the very things we were fighting against. And quite frankly, I found the protests a little boring— they were orderly and neat, and most of all, didn’t have any of the art, the marching bands and dancing and performance I was used to.

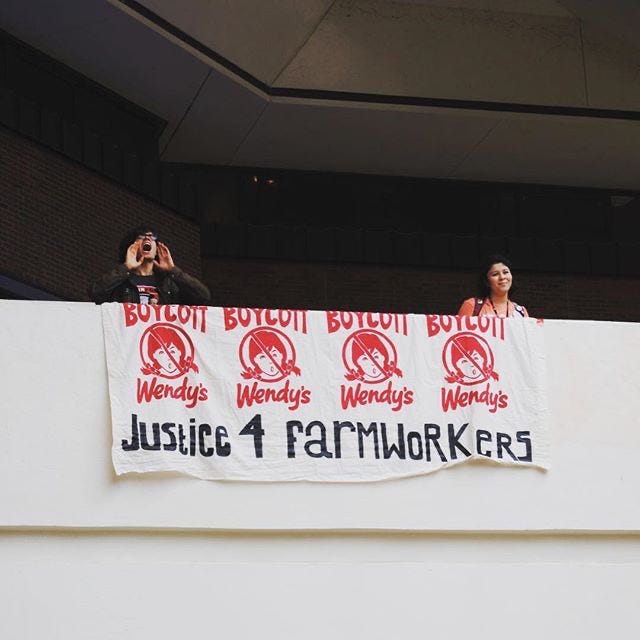

That was until I went to a protest in New York City organized by a group of farmworkers from Florida called the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, or CIW, in the spring of 2018. It was joyful and raucous, with people of all ages chanting in different languages and big puppets just like back home. The next semester, I took time off from school and interned with the CIW in Florida. It was grounding to be back amongst Latinxs, but most of all just to be amidst people who were fighting for justice day in and day out, and whose main concern was how much you were willing to throw down for the cause. It was intense, with 10-12 hour days, 6-7 days a week, and I definitely don’t want to romanticize that, but I learned a ton about organizing within the more formal constraints of an actual nonprofit. I was also encouraged to use my video and design skills, and over the course of my months there, I made a number of different videos for the Coalition, ranging from interviews targeting a faith-audience for funds, to animations of the organization’s budget for a grant proposal, to promoting an annual student organizing summit in a goofy video made with a bunch of the farmworkers’ kids. This was art of a different sort, also in resistance, but more measured and targeted. With the Coalition, I learned how important it is to find a movement-home, even if only for a while.1

Since then, I’ve graduated college, made a scattered collection of unfinished documentaries, short video-essays about queerness and Chile and distance, and written a fair number of poems as my thesis— enough for a book, in fact, which I’m working on now. The pandemic and this summer’s uprisings for Black Lives Matter, on the verge of graduating, turned me to thinking more seriously about the role of writing and the publishing industry itself. There was a lot of (Twitter) drama in the poetry world over the summer and into just this month, about the major publishing houses, and, in particular, one of the largest foundations in the poetry business, which has made blunder after blunder in trying to redress its history—and present—of racism, misogyny, colonization, ableism and queer-phobia. Even a small, self-proclaimed revolutionary queer press that I admire accepted a massive grant from Amazon, the bookstore-killer and labor abuser.

Online, I found other revolutionary poets, in particular, a trans woman of color named Jamie Berrout, writing about the necessity to move away from the nonprofit-model small press, to create mutual-aid printing cooperatives, where not only could we print books and zines—like the ones that had radicalized me as a kid in Santiago—, but posters and banners for protests, too. Where contributors and collaborators could be paid fairly while reinvesting enough to keep the operation running, without necessarily aspiring to grow any larger or gain outsized recognition. To leave space for so many others to grow alongside. I think what’s also really important about this is getting away from the traditional gatekeepers of publishing, and the way that the publishing industry is quite rotten to the core.2

Obviously this is utopian, a sort of socialization of poetry that I dream could spread, mutating, to other creative industries, but I think utopias are necessary, dreams are necessary, as acts of resistance that allow us to broaden the possibilities of alternative futures, to open wider the horizon. We need to dream to find the way out. And as I’m dreaming, I’ve begun self-publishing some writing in process, to foreground craft and imperfection, on an email list-serv, and supporting other creatives I admire on their Patreons and list servs, trying to contribute to a nascent circular economy. I don’t think this is necessarily radical or revolutionary, but I think it’s a step in the right direction.

Returning to Chile for the first time in two years this December, I found myself writing, several evenings in a row, just trying to register all that I was noticing and finding in the return. Once the frenzy subsided, I collected the pieces and reordered them some, into a poem-essay about having missed the revolution of October 2019, the one I felt we were planting and planning for since I began marching, way back in 2013. The essay was a sort of sequel, too, to a film I made in October of 2019, while trying to understand and sort through the immensity of feelings I was encountering experiencing the revolution from afar, over social media, endlessly scrolling to be up to date and see every angle possible. While that was heartbreaking, harrowing and hopeful for me, it was nothing compared to the pain of people I knew getting gassed and sprayed, or the ones I didn’t know getting shot-at, losing eyes and some getting killed, by cops. Being so far away and working predominantly in English, I question frequently my place to be speaking, and writing, offering my incompleteness to the world, or The Internet. Recognizing that this is probably no different than any of the thousands of artists who doubt themselves and their craft, I try to consciously address my subject matter from where I stand, knowing my place as well as I can, clearly situating myself with regards to what I’m thinking through. I’m doing my best to acknowledge that, without re-centering myself, in the films I’m editing, as well.

My hopes for the near future are to finish my book, as well as trying to actually start some sort of writing/creative/printing/farming community project. I’m working full time at the moment, saving up to be able to take the leap on such a project when the time is right. I’m learning how to make my creative methods and forms more closely resemble my politics, and how to garden.

And I’m really excited to be here with you all, to hear your thoughts and what you’ve been working on and learning. I’m happy to talk more about anything I’ve mentioned here, from documentary practice and ethics, to forms of organizing and protest art, to why farming is so important. But I’d mostly love to have a conversation— how do you think we can bring our ethics and aesthetics more closely into alignment? How can artists build community and break away from capitalist, white-supremacist structures3 that center the individual creator and don’t acknowledge often-extractive or exploitative modes of production? What is, or maybe should be, the role of universities in all of this?

I know these are big questions, and sometimes it’s better to start small. So, how are you doing? How are you resting and taking care of yourself and others? How is art nourishing you to keep fighting?

Thank you.

La poesía es un arma cargada de futuro

— Gabriel Celaya

An offering of a playlist for space and peace

Further References

1. Here’s a short documentary I made about a CIW protest some time after the internship, in which I was able to take a somewhat freer, more poetic approach:

2. An important reference on this point is Walter Benjamin’s 1934 essay “The Author as Producer,” https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1970/author-producer.htm, which Jamie Berrout has also written about: https://www.patreon.com/posts/why-poetry-431999553

Here are some readings/resources I’ve encountered lately(ish) that are shaping my political thought, in addition to all those linked above!

- Black Socialists of America

- On Woman as a Class, by Aly E

- Venus in Two Acts, by Saidiya Hartman

- No Humans Involved, by Sylvia Wynter

- A Feminist Approach to Decolonizing Anti-Racism, by Rita Dhamoon

- Poetry is Not a Luxury, by Audre Lorde

- Response to Race and the Poetic Avant-Garde, by Erica Hunt

- New Moon Report, by Ariana Reines

- Cento Between the Ending and the End, by Cameron Awkward-Rich