Grief and Protest

Hello dear,

This is a real long one. It’s two letters in one, really, and I’ve split them up— the first part is an approximately 7 minute read (cw: death, grief) and the second is more like 13 mins (Brown, protesting). I’m planning on recording myself reading them soon, so if you’d rather listen to my ~dramatic rendition~, please support me on Patreon! More about that at the end of the letter, but in short, I’m unemployed and could use any help as I'm trying to live off of my art a bit more. If you want the audio version for whatever reason, especially accessibility, and can’t afford a donation, just email me back and I’ll send a link to it once I record. It won’t be anything fancy (I need to promise myself that so I don’t do The Most), but I love reading and think it might be a nice thing. As always, thanks for reading, and much love.

I. Grief

It’s been a good, tumultuous, long time since I’ve written. I’ve been reading Octavia E. Butler’s Parable series (I love them and am terrified, inspired and distraught), and it’s interesting how they’re setup diaristically. There are often gaps of many months between the protagonist’s journal entries, but the story is still very complete and obviously compelling.

I think daily, or highly regular journaling, leads to more rumination and reflective, wandering expressions of thoughts, while erratic record-keeping is more plot-like, action-oriented. It’s like the difference between catching up with a friend after a long time and telling them everything you’ve been doing versus friends you talk to so often that when you talk it’s more about sharing the present, your thoughts, yourself. It’s been a full month since my last writing, more since I’ve sent writing out. We’ll see in which direction this goes.

My grandfather, Tata Pato, passed away a month and a half ago. He was my mother’s father, a hilarious, charming, kind old doctor (an OB-GYN, he delivered me!) who lived in the port city of Valparaíso. He loved the port. Whenever I visited we would spend hours sitting on his little balcony overlooking the harbor, watching ships come in and out, each reading our books. Then we would go out for a walk and he knew everyone in the neighborhood, or bantered with strangers as if he’d known them all his life. He was a flirt, in the ultimately harmless and funny yet occasionally uncomfortable and problematic way of old men. But he was always genuinely and constantly caring, generous, and easy to be around; he put you at ease with just a smile and a hug. There is much to be said about him, memories I need to preserve, but I don’t feel quite ready to write about him more. And what I can say feels terribly insufficient; this is all overly picturesque and yet lacking.

Mami wrote an incredibly poem for his funeral, which I keep coming back to. These words are so full and rich. I hope you cherish them:

O Captain!, my Captain!, capitán pirata, papito lindo,

Llegué hasta las ciudades fronterizas del Norte

Y en el Sur visité las riberas insalubres del mar

Mas no hallé en los confines de la tierra y del cielo

Lugar adonde se pueda huir dejando la tristeza atrás

— Liu K’o-chuang

Hace muchos años con mi entrañable amiga Delpis leíamos y leíamos este poema sin saber por qué. Hoy parece que por fin entiendo.

Mi papá que era pura alegría y luz. Que nos enseñó a desafiar la lógica y salir, en días de sol, a desfilar con paraguas; a marchar en fila india y repetir sus movimientos absurdos, para, de improviso, tocar un timbre cualquiera y salir corriendo.

Mi papá que comía manjar con manzanas y con casi todo, que se ponía calcetines y zapatos cambiados por su daltonismo y que era medio ciego de un ojo.

Mi papá, que era capaz de inventar una fórmula antes de decir que no la conocía.

Mi papá que hablaba inglés con acento de Boston.

Mi papá que tenía las manos largas y los pies chiquititos.

Mi papá que recitaba poemas por doquier y que era amigo de cuanto caminante se encontraba por los cerros de Valparaíso, tenía una herida en el alma.

Y hoy celebro, hoy celebramos que por fin se reencuentra con sus hijos tan queridos: Pato y Cata (y el Negrito lindo), a los que tanto extrañamos…y con sus papás, el Velita y la Welly, y con nuestra nana, la Ia, la viejita, y con sus hermanos tan queridos: Jaime y Jorge, y que todos bailan de lo lindo. Como esas fiestas que me contaba del viejo Valparaíso, con su papá arriba de las mesas bailando, y comen rico, delicioso y se abrazan y pintan el cielo que ya hoy (ayer) lucía de colores. Vuela alto papá. El más bello del mundo.

Santiago, 8 de abril 2021

A quick translation:

O Captain!, my Captain!, pirate captain, lovely papito,

I arrived to the border cities of the North

And in the South I visited the sea’s filthy shores

But I couldn’t find, at the ends of land and sky,

A place where I could run leaving sorrow behind

— Liu K’o-chuang

Many years ago with my dear friend Delpis we read and read this poem without knowing why. Today it seems I finally understand it.

My dad was pure joy and light. Teaching us to defy logic and go out, on sunny days, to parade with umbrellas; to march in single file copying his absurd motions, to suddenly ring a random doorbell and run off.

My dad who ate manjar with apples and nearly everything, who put his socks and shoes on switched around because he was color blind and half-blind in one eye.

My dad, who was capable of making a formula up before admitting he didn’t know it.

My dad, who spoke English with a Boston accent.

My dad, who had long hands and small feet.

My dad, who recited poems by the handful and was friends with every walker he encountered in the hills of Valparaíso, had a wound in his soul.

And today I celebrate, today we celebrate, because he is finally going to meet his beloved children again: Pato and Cata (and beautiful Negrito), whom we miss so... and his parents, Velita and Welly, and our nanny, Ia, la viejita, and his dear siblings: Jaime and Jorge, and they all dance from the beauty. Like those parties he told me about in the old Valparaíso, with his dad dancing atop the tables, and they eat sweet, deliciously, and they hug and paint the sky that now already (yesterday) glows in color. Fly high dad. The most beautiful in the world.

Santiago, April 8, 2021

The grief and pain have slowly eased. I don’t really know what it means, or feels like, to “fully process” a death or loss. Have I done that for Cata and Negro? Grandmother Priscilla? My earlier losses? Definitely not for Tata Pato, not yet. Though my memories of them all are fading already. Though I feel they might just be somewhere I haven’t found— not truly gone, merely away. I wonder if I would feel different about any of them if I’d been there in the moment of their last breaths. Moments? Breath? I don’t know when one dies. I don’t think it would make a difference.

I’ve had some lovely, sweet times in the last month, since the funeral I watched livestreamed on my laptop in the backyard while video calling my sister on the side. I insisted on wearing all black, mourning and trying to hold some semblance of solemnity and ritual in the uncertainty of loss and distance. But my family would have none of it. After Tata was lain in the ground, they carried us with them on their phones to Cata and Negro’s graves, and as we sat around feeling and remembering and crying, they began to joke, too, of course, as always, and soon we were all laughing. Tata Pato always enjoyed life so fully, we had to laugh in his honor.

I don’t know how to behave in mourning, and sometimes I wish we still had rigid old traditions to teach us what to do. How to dress, what to eat and not eat, how to honor and carry on without leaving our dead behind. But we also don’t need old rituals, we can imagine our own new ways of loving the gone, laughing. I absolutely do wish we had more time and space to grieve, though. That we could take time off work or school to sit with loss and be held and supported by our communities.

I’ve had some lovely, sweet times in the last month. We had an amazing bonfire for the full moon of the end of April, in Scorpio. I’ve started rollerblading and love it and have been riding around nonstop. I’ve been reading incredible, moving, inspiring books— besides the two Parable books (I finished the second last night!), a friend recommended The Freezer Door by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, and it changed me. Also To After That and Calamities by Renee Gladman; she’s a genius. I had a sweet visit from my partner, many little hikes and explorations around Rhode Island, delicious days of eating precious farmer’s market treats. My street, the whole neighborhood, burst into incredible bloom for two stunning spring weeks, and now the sun and heat is returning, bringing such life. Nearly everyone I know is vaccinated. Thank you for that, I’m so so grateful. So grateful to have new people around my fire, dear friends indoors, finally, to hug, to hug, to hug and hold. Thank you.

II. Protest

Three weeks ago now was May Day, Día Internacional del Trabajador. Ironically, I had to work for Brown’s Commencement Weekend, while my younger sibling Zoe arrived from Chile in the evening. That Sunday, May 2, was technically my graduation, though it was my third and by far least meaningful such ceremony for me (as a point-fiver) in the last year. On the Wednesday prior, my boss called to ask if I wouldn’t mind working on stage during the ceremony spraying alcohol on the microphones after each speaker. I thought it was kind of funny and said I wouldn’t mind. I texted a group chat of friends about it and then had a wild idea.

If they were allowing me on stage, front-and-center at such a massive public event, it was the perfect opportunity to stage a protest. I was planning on quitting in a month anyway, so I wouldn’t mind being fired, though I only had about a month or two of savings to live on afterward and no further plans. I texted this idea to the group, mostly joking, and they all were immediately supportive of it, probably also mostly joking. The more I thought about it, the more I felt I had to do it. I went back and forth about it for days, messaging more people to ask for their opinion and support. The primary abolitionist group on campus, Grasping at the Root, thought it would be a good action and were willing to back me up.

We talked over what would make the best messaging, and the many possible repercussions I might face. I grew increasingly certain of the need to do it as the day neared. I imagined not doing it, and quietly leaving my privileged position of access at Brown in a month, knowing I could’ve stood up to challenge the institution I’ve so grown to despise. The more I’ve thought about it and learned, the more I think universities must be abolished.

On the one hand, as an anarchist, it is obvious that the call is to abolish all institutions, all hierarchies, and universities are clearly incredibly hierarchical institutions. But part of me still believed in them—enough to stick through four, nearly five years, at one—and their mission of higher education. Of course, I still believe in higher education, but now I’m convinced universities are not a form of education we should be trying to save, reform, reproduce, or strengthen.

By protesting them through ways that appeal to the very power structure of the university—protesting in front of University Hall, sending letters, petitions, and messages of discontent to leadership—we legitimize their power and affirm their existence. We not only pour time and energy into these places that have already taken so much—land, labor, wealth—but also give them the very tools they need to continue evolving in liberally acceptable ways without changing their essential, destructive and extractive function. We help them appropriate and dilute radical ideas and practices without giving back to the organizers and oppressed people who created those ideas. We help them continue innovating the neoliberal project, masked in friendly language of diversity, equity, and inclusion. We help them continue gentrifying, dispossessing, and concentrating wealth back into the same hands. So many Brown students are immensely wealthy, and study to simply get a credential from the institution, enabling them to continue amassing wealth. They even trick themselves into thinking they need to work— often in tech, or finance, or the nonprofit industrial complex, or right back into academia.

I wanted to protest in some small, true way, that would hopefully not end up back on Brown’s homepage, appropriated through shiny photos as proof of student’s “commitment to change.” I wanted to disrupt, albeit in a lonely, possibly insignificant way.

I walked around all weekend doing my job diligently, putting in my good hours on Brown’s dirty dime. But underneath, I bubbled anxiously, titillated by the secret knowledge of what I was planning. I felt like a secret agent, as I’d imagined as a child. I think it’s right to have felt not only anxious but excited, in a playful way, by the upcoming action. Too often our actions and protests are merely draining and nerve-wracking, and the revolution should also be fun and pleasurable.

After their long day of traveling on Saturday, and my day of work, my sibling and I were both exhausted and needed rest, so we had a quiet night and went to bed early. I couldn’t quiet my mind, playing possible scenarios out over and over again in my head. What sort of protest should I do? Should I chant? If so, what, and when? How should I communicate my message? How long should I stay up on stage, and what would happen? Would they call security, drag me off, or let me tire myself out? What was I risking? Would I look like a fool? Was it all dumb and pointless, empty theatrics? What difference would it make? Would they sue me? I barely slept.

In the morning, I put on a ratty old black t-shirt and then, over top, an amazing black jumpsuit handed down from a friend. It was reassuring to feel her presence through the worn clothing. I lined my eyes with bold, black wings to draw strength from my own reflection in the mirror. Pulled on tall, heeled black leather boots. Alex did my hair in two braids down either side of my head. I felt like a thoroughly queer warrior.

The entire graduation ceremony happened twice, once in the morning and once in the afternoon, to reduce the density of the crowd. I took the morning as a trial run, calculating when would be best to stage my protest considering the different places I had to be on stage and the prepared videos that could be played to drown me out.

I went home for a light lunch between the ceremonies, forcing myself to eat through the nerves. I put on red lipstick beneath my mask, touched up my eyeliner: rituals for strength and embodiment. I walked back to the green and arrived quite early, so I lay down under some trees in a nearby quad to ground myself. I tried to still my anxious thoughts, but mostly just kept obsessively running over my plan.

Students in regalia started walking in and I took my position by the stage. The ceremony began once again, a procession of powerful people emerging from the depths of University Hall and taking their safely spaced-out seats above us. I consulted my folded and re-folded, highlighted and torn, run-of-show. Sashayed across the stage to spray the microphone after the chaplain’s opening prayer. During the first ceremony, the crowd had seemed to applaud a bit extra for me after my first, useless little spraying bit, but this time I was met with silence. Was it a less lively group this time around?

Most of my graduating friends seemed to be at this second ceremony, or at least the few I’d checked in with beforehand to give a vague heads-up of my plan would be. I hoped they would chant with me.

The student speeches were rousing and moving, particularly the first one. George Kubai, a biomedical engineering graduate, told his story of struggling to reach the Ivy League as the child of a single, African-immigrant mother— a story of “Black success” he dreams could “not [be] an anomaly,” if Brown students were only to go out and change the world by dreaming. I deeply agree with him about the power of dreaming as an “intimate act of resistance,” though I would emphasize more the importance of dreaming in community than his speech did. “I'm dreaming of challenging the very systems that allow us to see Black success as exceptional and not normal,” Kubai said of his story. Yes! This is exactly what we must dream of, I thought. Then he immediately continued: “We can dream together of a Brown University where African-American faces are not an oddity.” What?! Brown is an integral part of those systems! I felt betrayed, though not surprised. These speeches are approved by the university, after all.

I felt betrayed because in the world of freedom I’m dreaming of, institutions like Brown don’t exist at all. Carceral, tax-haven, land-stealing old paragons of whiteness and liberalism are not what I dream of for anybody. Kubai said we must dream of a world where students don’t feel imposter syndrome in the classroom— exactly! No one will feel imposter syndrome if we’re not trying to fit into institutions that never wanted us! I'm caught in a bind between recognizing the radicality, struggle, and importance of making space for oppressed people at these awful institutions, and critiquing their very existence. I'm deeply grateful to the students who came before us and made it possible, easier, to make it through somewhere like Brown. But what could we achieve if we were not trying to reform institutions built on oppression, and rather finding our own, radical ways of educating and learning together?

“For those moments [of hopelessness] I remind us,” Kubai said as he was concluding, “of the little girl who dreams to be in the seats that we are all in today, but this country has already told her no on the basis of her skin.” What was this reminder of, truly? Of the amazing opportunity we’ve been given, us chosen, lucky, few, who were allowed into the exclusive institution? To fill its quotas of diversity, while rich kids and legacy kids sauntered in without questioning? That little girl gives me hope when she is not dreaming of an institution that would deny her humanity, or working her ass off to prove it. I agree that Kubai's story should not be the exception, but how can we dream of a more inclusive Brown if it is built on exclusivity? How can we dream of everyone having an equal shot at getting into Brown if it continues to have a 6.6% and dropping acceptance rate? Brown must cease to exist.

I pause to reflect on this speech because much of it resonated with me. I don't mean to attack it merely for critique's sake, but to tease it apart because I'm still trying to clearly see and understand these deeply-ingrained thought patterns I, too, have internalized. I came to Brown for many reasons; I believed in its worth, deep down. I don't anymore. I'm still trying to let go.

Despite dreaming of challenging the very systems of white supremacy (though they weren't named as such), Kubai's speech still singled out Brown students, and our white-supremacist credentials from Brown, as world-saviors: “When we feel hopeless, I say again, dare to dream, class of 2021. We will be the ones who will dream of the better world that will come to be.” I write this full of questions, contradictions, barely able to contend with my own complicity in the many multiple systems of oppression Brown upholds. I, too, stuck it through for my degree, and took Brown’s money when it was offered. I, too, want to make a difference in the world. Here I am, spending my time filling it with more credentialed words.

But I believe in abundance, not scarcity— that is why I reject the university. I don’t believe in the false scarcity of its admission rates, or the false scarcity of its claims to excellence and its very real chokehold on knowledge. I believe I must give everything I have, including what I’ve gotten from this rotten institution, to join the struggle that has existed long before me and will continue long after. I don’t believe my dreams will change the world, but I believe joining my dreaming to those who haven’t been approved by the university, or held a steady job, or voted in every, or any, election, will get us closer to freedom. I don’t think my dreams should be exceptional or strange at all. “What will this world look like because you have chosen to dream?,” Kubai concluded. I hope it looks like a world without Brown, I thought, as I prepared to go up and spray his microphone with alcohol.

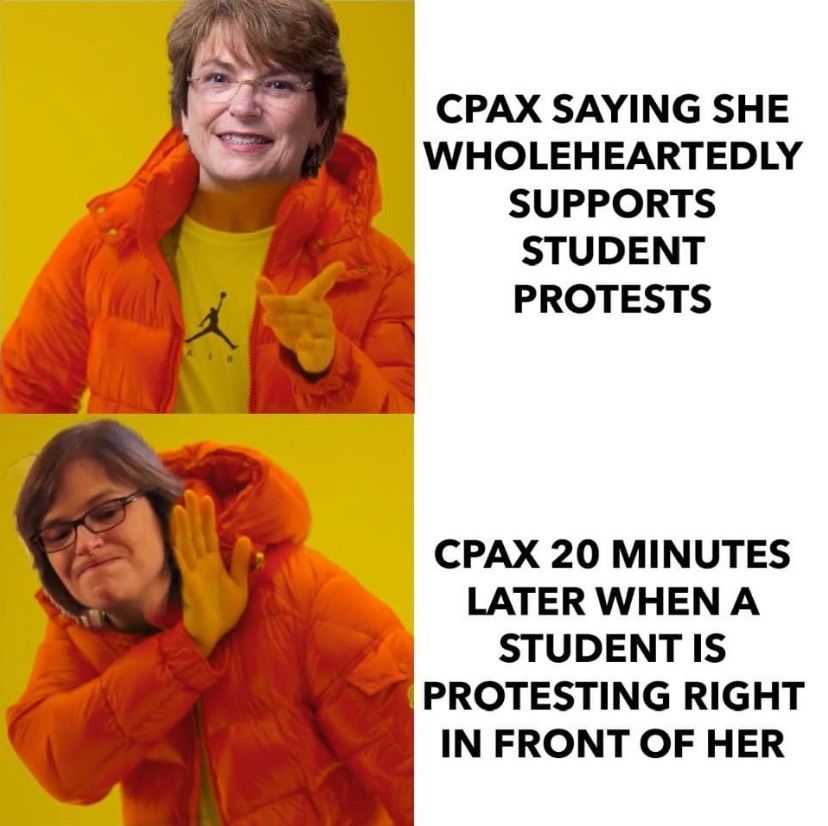

Christina Paxson, too, had rousing and inspiring words of change to impart, though she claimed to be “changing the script” from the usual graduation speech, since during the pandemic “all of the scripts that we use to guide our lives just…flew out the window.” She went on to talk about the normal script of an academic year: “Students arrive over Labor Day weekend. Family weekend and football games are in October. The MLK Lecture is in February. Student protests, which I wholeheartedly respect, are usually in April.” Lol. We would see about that.

It was almost refreshing to see such an open admission of how the university appropriates, turns around, and sells student activism back as a part of its branding, while dead-ending all actual demands in the perpetual hellfire of working groups and committees. They’ve even had the audacity, lately, to claim how content and proud they are about the level of “student buy-in” to the university’s supposedly top-down, administration-driven Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Action Plan— as though it hadn’t been student protesting and demands that pushed the administration to ever do something about diversity in the first place! It’s infuriating to see the hard work of student organizers turned right around to give the institution credibility where it once resisted change. Neoliberalism at its finest.

After Paxson’s speech, there were a few more formalities and a heartwarming video of Brown grads gushing about their last four years. I wish I could’ve gone up right after Paxson’s speech, to really drill home her lies, but they would’ve just played the video over me. Instead, I waited for the video to wrap up, then walked up and sprayed one last time. At that point, it wasn’t even necessary; I’d completed my duties for the day. Paxson began standing up to the mic but I left my spray bottle on the edge of the podium and pulled down the top of my jumpsuit. It hung around my waist, revealing the back of the black shirt, which read: “Abolish Brown: Land Back + Reparations Now.” I turned around at the front of the stage so the message was to the audience, stood for a second, and began chanting. “Cops off campus! Cops off campus!” I closed my eyes, trying to steady my heart and breath and solitary voice. There was so much else I wanted to say— “Boycott, Divest, and Sanction! Warren Kanders must go! Pay your fucking taxes!!” But I knew I would get lost and had no chance of garnering audience support if I changed chants.

As it was, no one joined me. I wish I’d had more time to get friends on board; perhaps with some people in the audience we could’ve gotten a good amount of people making noise. I kept going, though, losing steam, and opened my eyes to see Paxson staring me straight in the face. It was terrifying. She looked so stony and emotionless, nearly bored. I suppose this was her way of projecting strength. Once we locked eyes, she said something to me along the lines of, “we’re in the middle of a celebration. What do you think you're doing?” And though I quickly looked up and closed my eyes again, she’d said exactly the right thing to get me in my head. My voice cracked horribly, and I knew I couldn’t keep it up much longer. I felt terrified, and terribly alone. What do you think you’re doing? Who do you think you are? Don’t you see you’re alone here? I heard her voice in my head. I weakly pumped a fist in the air, and not knowing what to do, walked back off stage, barely registering the cheers that emerged from the audience. As I speed walked away from the crowd, some friends yelled my name in support. I didn’t know if security guards would be waiting for me at the edge of the green, if I’d be allowed to go, if the protest had registered in the live stream at all. But I had done it. I made it home fine, thankfully. The next day, I was fired.

Love,

Nico

GAtR supports the worker's protest action at #BrownU #Commencement yesterday, who was a #Classof2021 graduating student and was fired afterward. The worker's statement is: "Abolish Brown: Land Back + Reparations Now. #CopsOffCampus."

— Grasping at the Root (@wegrasptheroot) May 3, 2021

P.S. Even writing this, I’m afraid of giving them more material with which to retaliate, if they wish to. There is more to be said for the days since— of the anger and fear I was told I inspired, gladly; of camping with my siblings by a river in the Catskills and letting it wash away; of trying to figure out how to survive for a bit without a job, because I can’t think about working in an office, on my computer, all day again. I’m going to see how I long I can make it on my little savings and support through Patreon, so if you can, I appreciate any and all help. I’m going to continue making most of my writing archive available for free online, though I’ll keep more sensitive, personal pieces like this and my poetry-in-progress patron-only. The email listserv will also receive everything, as I believe in accessibility and the free circulation of culture. If you could spread the word about my writing, and let people know they only need to ask for free access if they can’t afford to support, that would be amazing. Thank you.